Yom Kippur special: The world's most beautiful synagogues

Despite the

very modest demands of the Halacha for the design of Jewish houses of

prayer, extremely impressive buildings have been erected around the

world over the years. Here's just a peek into eight of these magnificent

synagogues.

Lilit Wagner

It is well known that

the Halacha, and rabbis' halachic rulings, dictate almost every aspect

of Jewish life. But when it comes to the synagogue, which is supposed to

be the center of Jewish activity in the community, there are no

halachic rulings dictating what it should look like and what are the

architectural rules it should be built according to. The only

instructions mention a platform in the middle and a Holy Ark facing the

Land of Israel.

The

Shulchan Aruch code of Jewish Law suggests having 12 windows partly

facing Jerusalem, with the sky reflected through them, so that the

worshippers can direct their hearts as they look at the sky. But apart

from these instructions, the synagogue may be round or triangular,

symmetric or asymmetric, as the architect pleases. It can also be made

of wood, stone, iron or clay, and as long as there are 10 men present

for a quorum - a proper prayer can take place.

spite the very modest demands, extremely impressive buildings have

been erected around the world over the years in places with thriving

Jewish communities, which sought to demonstrate their presence through

an impressive Jewish center, both in terms of its external architecture

and the ornaments, chandeliers and furniture within it.

Here are several examples of centuries-old buildings, which are still

considered some of the most beautiful synagogues in the world, and

still serve - even as the Jewish community around them dwindles - as

museums of the Jewish culture which used to thrive there.

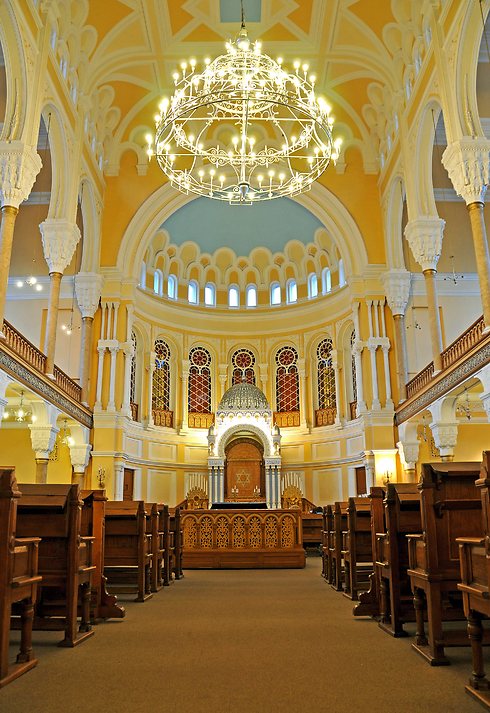

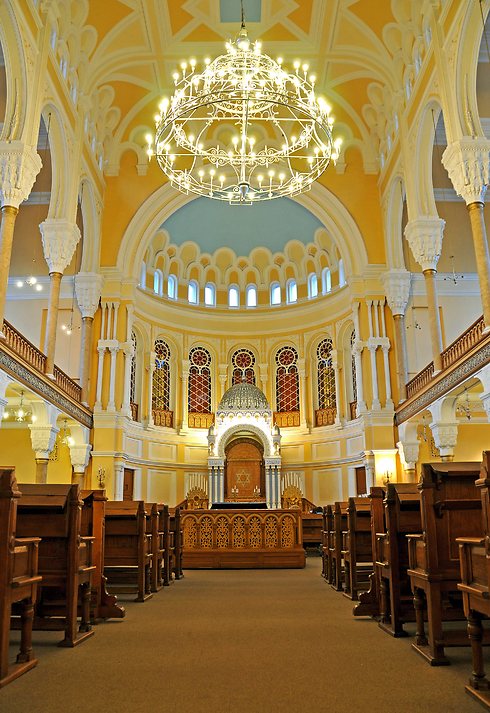

The Grand Choral is the second largest synagogue in Europe. It was

built between 1880 and 1888 after Tsar Alexander II cancelled some of

the restrictions on Jews' residence in St. Petersburg and allowed Jews

who served in the army, academics, senior merchants and technicians to

live in the city and in other big cities.

Photo: Dennis Jarvis/ Flickr

Photo: Dennis Jarvis/ Flickr

The construction of the synagogue, which served the entire community

in the capital of Tsarist Russia, took eight years. Famous Russian

architect Vladimir Vasilievich Stasov supervised the design, which drew

its inspiration from Berlin's New Synagogue, Arabesque motifs and

Byzantine elements.

In 1999, Edmond Safra's family donated $5 million for the

synagogue's renovation, and it is considered today one of the city's

architectural pearls.

The Dohány Street Synagogue is the largest in Europe and the second

largest in the world, and can seat up to 3,000 worshippers. It was built

between 1854 and 1859 at the heart of a neighborhood in which Theodore

Herzl's house of birth stood.

Photo: Galit Kosovsky

Photo: Galit Kosovsky

The building is filled with Jewish symbols, mainly Stars of David

which appear both in the stones and on the vitrage windows. The roof is

topped by the Tables of the Covenant with the Ten Commandments engraved

on them. The Bible verse "Then have them make a sanctuary for me, and I

will dwell among them" (Exodus 25:8) appears at the front of the

building facing the main street.

Upon the rise of Nazism, anti-Semitism in Hungary grew, and

during World War II the synagogue was used as a stable and as the German

army's radio communication base.

The Jewish community in Hungary has grown significantly smaller

over the years, due to the immigration to Israel and the assimilation

process, but the Great Synagogue of Budapest remains one of the most

famous tourist attractions in the city. It is part of a complex which

includes a museum on the history of the city's Jews, a Jewish cemetery

and a memorial site for the 564,500 Hungarian Jews who were murdered in

the Holocaust.

The Neue

Synagoge was built between 1859 and 1866 as the Jewish community's

center of religious life and culture in Berlin. Because of the Arab

elements in its design, and its resemblance to the Alahambra Palace in

Granada, Spain, it was considered one of the most important buildings in

Berlin in the second half of the 19th century.

Photo: AP

Photo: AP

The original building - with its golden dome and the main hall

which seated up to 3,000 people - was torched during the Kristallnacht

pogrom in 1938, although it was not completely burned. It sustained a

lot of damage in the Allies' bombings during World War II and was

demolished in 1958.

The synagogue's reconstruction work began only after the Berlin

Wall was torn down, and in May 1995 it resumed its role as a Jewish

cultural center, although it did not restore the glory of the 19th

century.

The synagogue in Bulgaria's capital is the third largest synagogue in

Europe. It is 31 meters high and can seat 1,300 worshippers in its main

prayer hall. It was opened for Bulgaria's Sephardic community in a

festive ceremony in September 1909, in the presence of Tsar Ferdinand I

of Bulgaria, after nine years of construction.

Photo: Rachel Titiriga/ Flickr

Photo: Rachel Titiriga/ Flickr

The architectural style is Moorish with Arab elements, inspired

by the Leopoldstädter Tempel in Vienna. The interior features many

columns of Carrara marble, Venetian mosaics and a chandelier in the

middle of the hall, which weighs 1.7 tons and is considered the biggest

in the Balkans. The rumor said that the gold covering the chandelier

came from the biblical Land of Israel.

Today the synagogue houses the Jewish Museum of History, which

includes the Jewish communities in Bulgaria before and after the

Holocaust.

This was the first synagogue built in the United States by Jews from

Eastern Europe. The building was designed by brothers Peter and Francis

William Herter. When it opened in New York's Lower East Side in 1887,

the media would stop praising its beauty, the high ceiling, the

stained-glass rose windows, the magnificent copper designs and the

handmade wall paintings.

Photo: Librarygroove/ Flickr

Photo: Librarygroove/ Flickr

For 50 years, the place served as a meeting point for the new

immigrants arriving at the new world. There, they received a hot meal,

information on odd jobs, apartments or any other need raised by the

community. Over time, the community dwindled and the place was deserted

by the end of the 20th century.

In 1996, the Eldridge Street Synagogue was designated a National

Historic Landmark, and in December 2007, after 20 years of renovation

that cost $20 million, it reopened to the public.

At

the end of the 19th century, during the reconstruction of Prague's

Jewish Quarter, the "Society for the Construction of a New Temple"

purchased an old house on Jerusalem Street as a site for a new synagogue

that would serve the community. The construction work began in 1905,

and the synagogue was dedicated during the holiday of Simchat Torah in

1906.

It was designed in Moorish Revival form with Art Nouveau

decoration. The entrance features a large Muslim arch and a large window

with a Star of David at its center. The Bible verse "This is the

gateway to the Lord – the righteous shall enter through it" (Psalm

118:20) appears above the arch. The main hall has seven arches on

pillars supporting the building, and the women's gallery features

vitrage windows and many copper chandeliers.

During World War II, the building was used as a storeroom, and as a

result it did not sustain too much damage. In 2003, a parchment scroll

was found in the synagogue, signed by the people involved in its

construction with the following text: "May this temple survive many

centuries and testify, even in the distant future, to the devout souls

of its founders. May it fully serve its purpose for all time: to bring

together worshippers in a place where they can uplift their souls to the

Creator. May the Lord give! Done in Prague, on the 16th of September of

1906."

The synagogue still serves Prague's Jewish community and

features a permanent exhibit which surveys the history of the Czech

Jewry in the years after World War II.

The Jakab and Komor Square Synagogue in Subotica was built in 1902

during the administration of the Kingdom of Hungary (part of

Austria-Hungary). Hungarian architects Marcell Komor and Dezső Jakab

were responsible for the design, and it is considered to this very day

one of the finest surviving pieces of religious architecture in the art

nouveau style, with its concrete and steel construction, mixed with

ornaments from the popular Hungarian culture.

Photo: Klovovir/ Flickr

Photo: Klovovir/ Flickr

Its main dome is surrounded by smaller domes on four corners, and the

interior design features golden wall decorations, wall paintings and

stained-glass windows.

During the synagogue's construction, Subotica had a thriving Jewish

community of some 3,000 members, which was almost completely annihilated

during World War II. But although there are not enough worshippers left

in the area, the building itself remains intact and has preserved its

important role in the city's history. When there was no Jewish community

left in the area, the building was used by the Subotica National

Theater.

Since the destruction of the Jewish neighborhood in Florence in 1848,

the community members had sought to build a central synagogue which

would serve all of the city's Jews. But the plans were only realized 30

years later, thank to a large donation from the president's community,

David Levi, who left his estate and property for the construction of a

synagogue which would be "worthy of Florence's beauty."

Photo: Harshlight/ Flickr

Photo: Harshlight/ Flickr

The synagogue was built in a style which was particularly

popular those days, a combination of Moorish and Byzantine architecture.

The synagogue's roof has a central dome raised on pendentives is

reminiscent of the Hagia Sophia. The corner towers are topped with

horseshoe-arched towers themselves topped with onion domes in the

Moorish Revival style.

The synagogue is lit by 16 windows from above, and additional

light comes from large windows on the eastern side of the building. The

eastern part of the roof features half a dome which symbolizes the

direction of the prayer.

The

synagogue is located at the center of a public garden with exotic

plants, and a magnificent Moorish style gate, creating an atmosphere of

oriental splendor. The garden includes memorial stones, including one

featuring the names of the Jews of Florence who were murdered in the

Holocaust, a monument for the Jews of Florence who were killed during

World War I while serving in the Italian army, and a memorial for three

Florence Jews who were killed in Israel while fighting the War of

Independence. Arie Avisar, who did a lot to restore the community after

World War II, received his own monument.

The history of Florence's Jewish community is commemorated in an

exhibition at the museum on the synagogue's first floor. The exhibition

is divided into two parts: One features the history of Florence's Jews,

and the other presents different items used for holy ceremonies and

holidays.

|